The Spine: General Structure

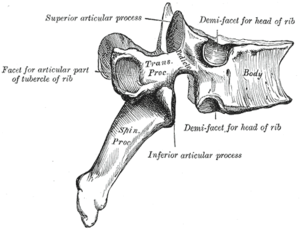

A typical vertebra consists of two essential parts: an anterior (front) segment, which is the vertebral body; and a posterior part, the vertebral or neural arch, which encloses the vertebral foramen. The vertebral arch is formed by a pair of pedicles and a pair of laminae, and supports seven processes, four articular, two transverse, and one posterior.

The Spine: The Vertebrae

Vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the individual bones that make up the vertebral column (aka spine), a flexuous and flexible column. There are thirty-three (33) vertebrae in humans, including the five that are fused to form the sacrum (the others are separated by intervertebral discs) and the four coccygeal bones which form the tailbone. The upper three regions comprise the remaining 24, and are grouped under the names cervical (7 vertebrae), thoracic (12 vertebrae) and lumbar (5 vertebrae), according to the regions they occupy. This number is sometimes increased by an additional vertebra in one region, or it may be diminished in one region, the deficiency often being supplied by an additional vertebra in another. The number of cervical vertebrae is, however, very rarely increased or diminished.

With the exception of the first and second cervical, the true or movable vertebrae (the upper three regions) present certain common characteristics which are best studied by examining one from the middle of the thoracic region.

When the vertebrae are articulated with each other, the bodies form a strong pillar for the support of the head and trunk, and the vertebral foramina constitute a canal for the protection of the medulla spinalis (spinal cord or spinal column), while between every pair of vertebrae are two apertures, the intervertebral foramina, one on either side, for the transmission of the spinal nerves and vessels.

Two transverse processes and one spinous process are posterior to (behind) the vertebral body. The spinous process comes out the back, one transverse process comes out the left, and one on the right. The spinous processes of the cervical and lumbar regions can be felt through the skin. Superior and inferior articular facets on each vertebra act to restrict the range of movement possible.

The Spine: The Cervical Vertebrae

These are generally small and delicate. Their spinous processes are short (with the exception of C7 which has the first palpable spinous process), and often split. Numbered top-to-bottom from C1-C7, atlas (C1) and axis (C2), are the vertebrae that allow the neck so much rotation. Specifically, the atlas allows the skull to move up and down, while the axis allows the upper neck to twist left and right. The axis also houses the first intervertebral disk of the spinal, which ends in the sacrum.

The Spine: Thoracic Vertebrae

Their spinous processes point downwards, and are long relative to those in other regions. They have surfaces that articulate with the ribs. Some rotation can occur between the thoracic vertebrae, but their connection with the rib cage prevents much flexion or other excursion.

The Spine: Lumbar Vertebrae

These vertebrae are very robust in construction, as they must support more weight than other vertebrae. They allow significant flexion and extension, moderate lateral flexion (sidebending), and a small degree of rotation. The discs between these vertebrae create a lumbar lordosis (curvature that is concave posteriorly) in the human spine.

The Spine: Vertebral Development

During the fourth week of embryonic development, the sclerotomes shift their position to surround the spinal cord and the notochord. The sclerotome is made of mesoderm and originates from the ventromedial part of the somites. This column of tissue has a segmented appearance, with alternating areas of dense and less dense areas.

As the sclerotome develops, it condenses further eventually developing into the vertebral body. Development of the appropriate shapes of the vertebral bodies is regulated by HOX genes.

The less dense tissue that separates the sclerotome segments develop into the intervertebral discs.

The notochord disappears in the sclerotome (vertebral body) segments, but will persist in the region of the intervertebral discs as the nucleus pulposus. The nucleus pulposus and the fibers of the annulus fibrosus make up the intervertebral disc.

The primary curves (thoracic and sacral curvatures) form during fetal development. The secondary curves develop after birth. The cervical curvature forms as a result of lifting the head and the lumbar curvature forms as a result of walking.

There are various defects associated with vertebral development. Scoliosis can result from improper fusion of the vertebrae. In Klippel-Feil anomaly patients have fewer than normal cervical vertebrae, along with other associated birth defects. One of the most serious defects is failure of the vertebral arches to fuse. This results in a condition called spina bifida. There are several variations of spina bifida that reflect the severity of the defect.